The Story of Hüseyin Aksoy

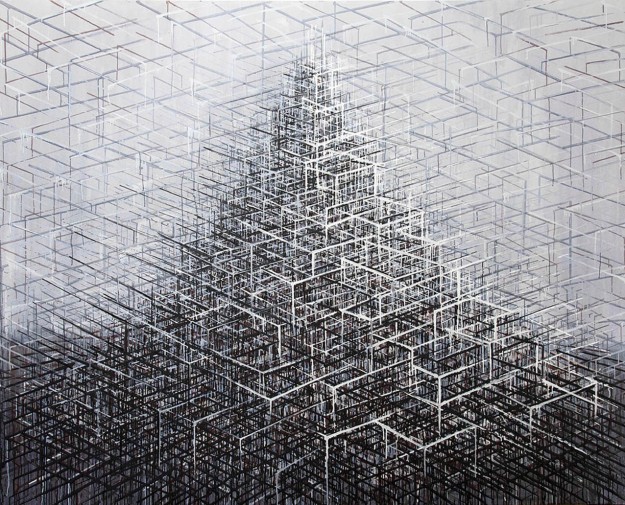

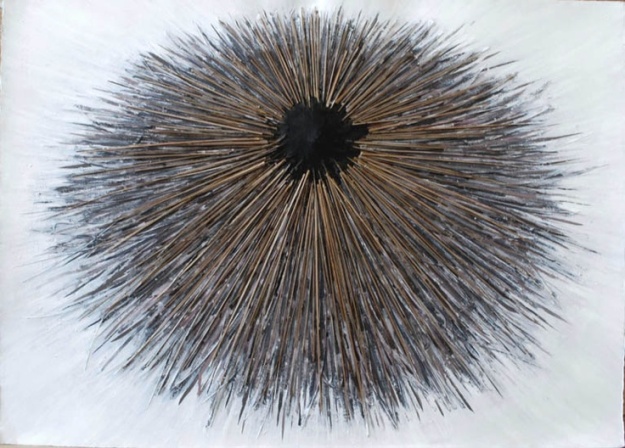

“I work as an alchemist who believes that art is experimental by working and who doesn’t want to limit himself to any material while working.”

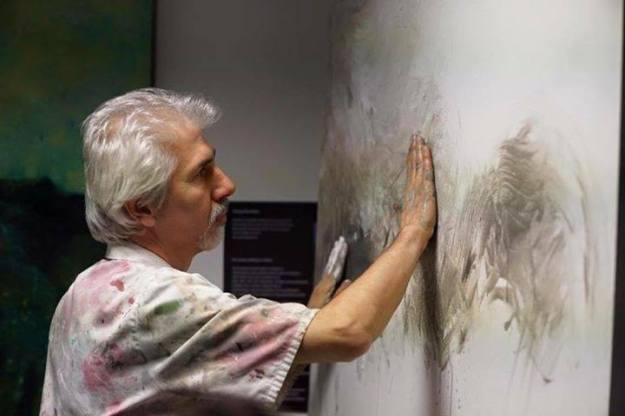

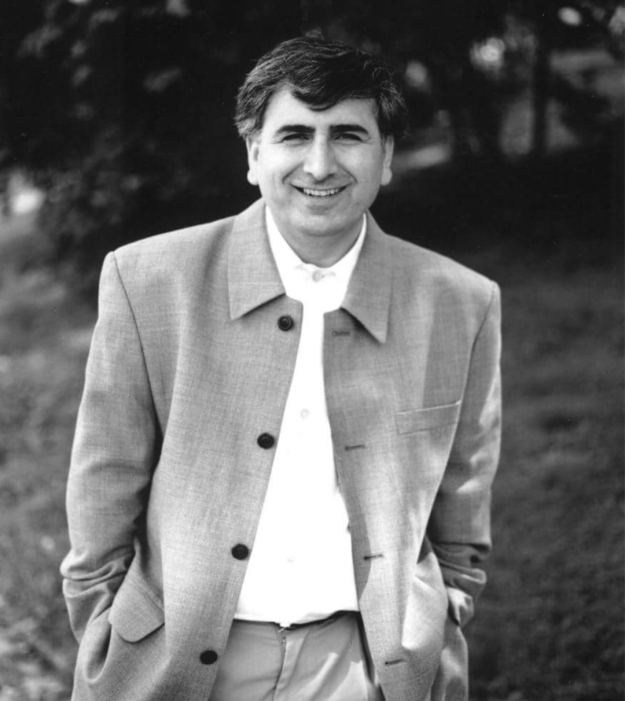

Today we want to share the story of a young artist called Hüseyin Aksoy. Hüseyin was born in Mardin(1996). His passion for Art started at an early age ;

He is the son of an 8-headed family. In 2015 he moved to Istanbul and started to study and completed his undergraduate education in Marmara University of Fine Arts A.E.F. at the Painting Department and also participated in many competitions and exhibitions. He took part in group exhibitions in Taiwan, Prag etc. In 2019 he graduated and since then he’s been working as an independent artist who is already selling his works.

“I didn’t start to do art, I actually dealt with the question of how to do it first, and then I started to question the meaning of what I did, I can say I started like that.”

“Hüseyin, someone, who first sees your work would get amazed by the details. They look like photography. What represents your work, and how would you describe it? “, Rengîn to Hüseyin.

“It changes. Sometimes I start working without thinking about the topic. These days I am inspired by a lot of things. Some of my topics are taken from the history and inspired by daily life and current changes happening in the world. I try to emphasize the topics like a social truth and try to show them that reality to express another reality from a political perspective. I try to uncover what we are seeing in the society and give it a “bare” reality to see. I use my art to show the reality from a different perspective, especially political-historical events. I try to show that “seeing “ is not an “ optical” but “ ideological “ process. I want my work to question the thinking of the audience. There is a word I like very much – art doesn’t answer and ask questions – I think I defend it.”

“The Last supper ”

Audio Link https:// http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WHwRsc7evNw

by addressing the photographic archives of the dengbej Artist da vinci’s ‚ last supper refers to ‚işine. In doing so, the eyes of the phenomenon represents the third world allows you to look at it again. This audio troubadours (dengbej) melodies object associated with the image, sound, between reality, referring to areas of the sensory version images. In this way there has been track image with images of the works constructed by cultural interact as it also provides sensory experience. The connotation and cultural norms as dolayımlı overas you explore the anachronistic thing spread anti-chronological placing to the context ‚ timelessness ‚ and ‚ just in time ındal ‚ tries to do the highlighting. But a settled culture in almost all households of the same formal properties of cultural object, settled on a common social memory, appreciation and value judgment. It’s culture, the specific objective of everyday life …

“Where do you get your inspiration from? “

“Inspiration is something I don’t believe in very much, I only believe in impulses. But I was for sure inspired by artists and art disciplines, of course, cinema, photography inspired me.” Hüseyin to Rengîn.

What about our culture and your roots about kurdish artist. Does it affect you being a kurd in Turkey and what do you think about the term “kurdish artist”?

“It is a privilege for me to deal with art as a Kurd. I belong to a group of people who have suffered persecution throughout history. Being a Kurdish artist is a state of outcry against all atrocities. As Emile Zola said, I came to live loudly as an artist. But I think there is nothing like kurdish art. It might be more accurate to call it Eastern art, not Kurdish art. I find the situation of Kurdish artists in Eastern art good. Every day it is getting even better. And we started to open up more to the world. This is a pleasure for me, too. Being Kurdish is for me to be a free person with a rich geography, a unique language and art.

“Does it become a priority for you to say I am kurdish?”

“I don’t say it if no one asks me, because it is not important for me. I would like to be an artist who doesn’t really takes parts in a cultural and political category.

The young artist had his last exhibition this year in MixerArts but he is looking forward to do more in the future. His plans on his work will continue. In the future he is looking forward to visiting Vienna and work further in film and photography.

“Hüseyin, thank you for the interview. One last Question; what do you think about Rengîn?”

I thank you! It was a pleasure. I think Rengin could be very helpful, especially to the new established artists and to the eastern art scene. I sincerely wish this kind of magazines would increase and more platforms are being created, where artists can exchange dialogues.Thank you for giving me the chance to be a part of this project. Im looking forward to reading more of Rengin.

Hüseyin AKSOY // Instagram: @hsyn.aksy

Interview by Dilan TAS