The story of Faek Rasul

„The traces will hurt as long as you don’t speak about them”

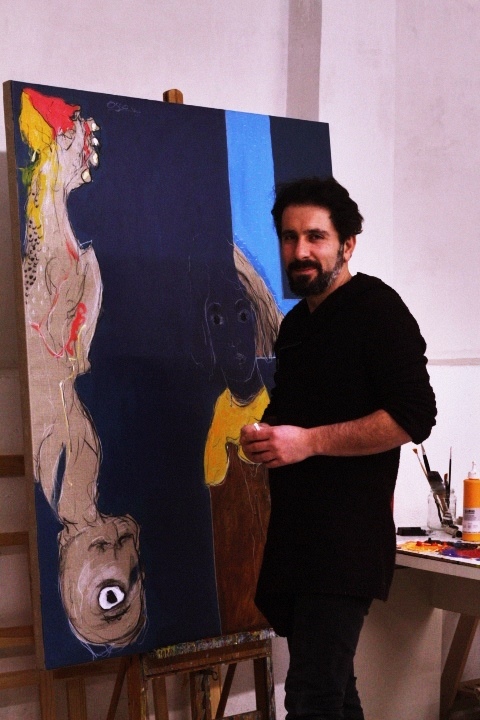

Rengîn had the luck to meet one of the most well known famous artists and curators Faek Rasul.

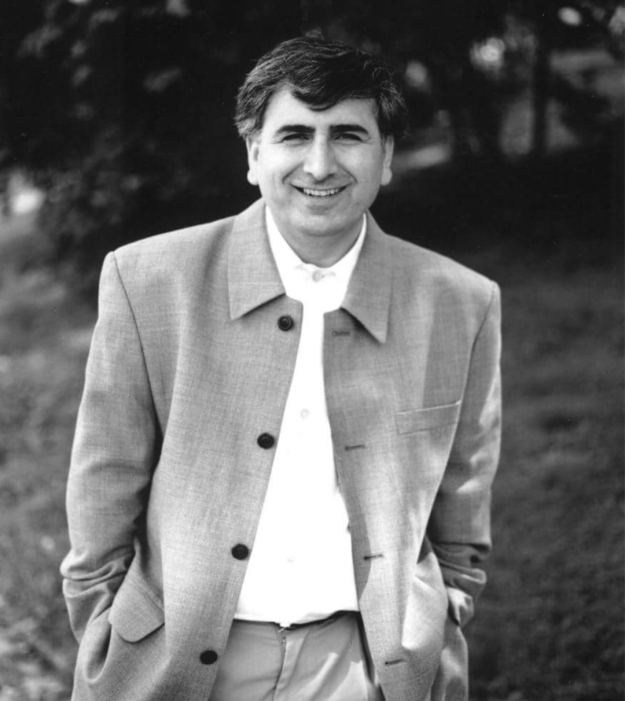

Faek Rasul is born in year 1955 in Kirkuk Kurdistan/Irak. In year 1980 he got his Diplom in the Institute of Fine Arts in Bagdad.

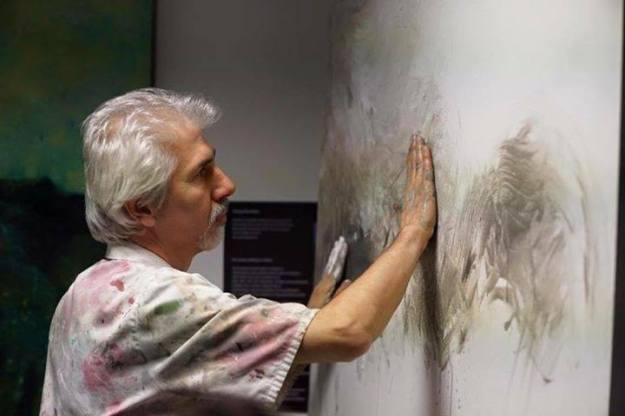

He captures the human as a whole with all of its dreams, hopes, fears, desires and passions. For him people become the synonym of being. He unveils powers, which lie behind the visible reality. Here one cannot talk about dismembered bodies or disintegrated spaces any more, but about the „total act“ and the „total picture“.

“When I feel the need to speak I paint” – Faek Rasul

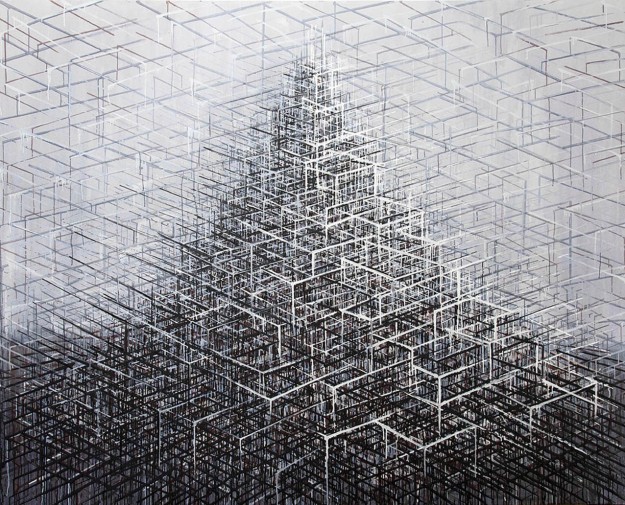

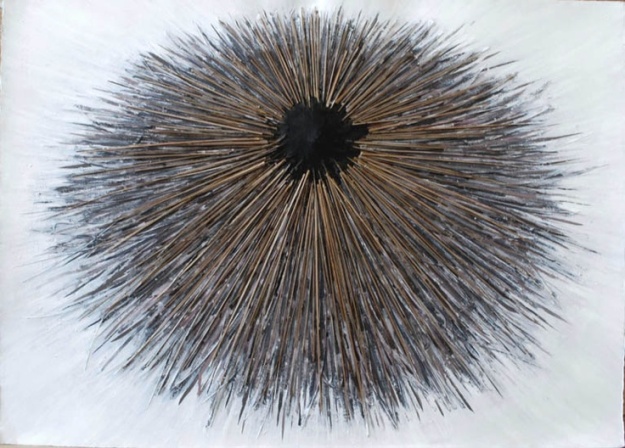

Faek Rasul’s paintings are in four different phases of development (Black and White, Violet Acts, Gravestone, Myth) They remind us of things, which he cannot or doesn’t want to express through the spoken words.

Not only words also numbers and scripts are his way the express himself. The numbers are derived from a mathematical whole and are developed into an aesthetic structure; and the writings, originating from a collective memory, are transformed into an individual memory.

“The life you are seeking you will never find” – Faek Rasul

The Origin of Faek Rasul’s paintings and technique is comprised of a number of personal experiences, which are for example his imprisonment in Irak because of his membership in kurdish resistance against Saddam Hussein. However, Faek Rasul’s employment for literature and painting leads to an inner disruption of his identity. Time in prison prompts his decision to paint and simultaneously prompts yet another point of refrence for his artistic creations.

Traces, remembrances or talismans are what Faek Rasul calls his paintings. He creates minimalistic, reduced works, like evocations and approaches to the irreducible, incalculable openness and unpredictability of human life and the future with the focus and sensitive use of his materials using mostly sand, color and employing hermetic signs: “Sand as Emblem of Transience, Beauty from Oriental Tradition and the Aesthetics of every day life”

In 1987, the year the political persecution of Kurds in Iraq escalated to finally end in genocide, he succeeded to flee to Austria from Iran. In over 25 years of artistic work in Austria, Faek Rasul created an array of picture series in varying stiles which he presented in numerous exhibitions in Europe, Eastern Asia and South America.

Since over 20 years he also works as a curator and since year 2000 as a gallery manager. At this time he manages the “Kleine Galerie” in Vienna. He has exhibited a line-up of some of the most important international artists.

Faek Rasul never ceased to paint; he dedicated his life to art. To the question “What do you think about being Kurdish and a Kurdish artist he says: “After over 25 years in Exile he says that “if you live somewhere else for 20 years than you are a part of it. – I always say that I am a Viennese.”

Faek Rasul is still active as a painter and curator and his future plans are to curate a big international Exhibition this year with international artists all over the world.

Thanks for the interview!

Website : http://www.faekrasul.com

Interview by Dilan Tas